A New Witch’s Introduction to Casting Spells and Using Spell Kits

Did you know that spell-casting is one of the oldest spiritual practices in the world? That’s right! Ancient civilizations dating back to the first millennium

THE GYPSIES,

NARRATIVE AND DRAMATIC POEM.

A noisy band of gypsies is wandering through. Bessarabia. Today they will pitch their ragged tents on the banks of the river. Sweet as freedom is their nights’ rest, peaceful their slumber.

Between the cartwheels, half screened by rugs burns a fire around which the family is preparing supper. In the open fields graze the horses, and behind the tents, a tame bear lies free. In the heart of the desert, all is a movement with the preparations for the morning’s march, with the songs of the women, the cries of the children, and the sound of the itinerant anvil. But soon upon the wandering band falls the silence of sleep, and the stillness of the desert is broken only by the barking of the dogs and the neighing of the horses.

The fires are everywhere extinguished, all is calm; the moon shines solitary in the sky, shedding its light over the silent camp.

In one of the tents is an old man who does not sleep, but remains seated by the embers, warming himself by their last glow. He gazes into the distant steppes, which are now wrapped in the mists of night. His youthful daughter has wandered into the distant plains. She is accustomed to her wild freedom; she will return. But night wears on, and the moon in the distant clouds is about to set. Zemphira tarries, and the old man’s supper is getting cold. But here she comes, and, following in her footsteps, a youth, a stranger to the old gypsy.

“Father,” says the maiden, “I bring a guest; I found him beyond the tombs in the steppes, and I have invited him to the camp for the night. He wishes to become a gypsy-like us. He is a fugitive from the law. But I will be his companion. He is ready to follow wherever I lead.”

The Old Gypsy: “I am glad. Stay in the shelter of our camp till morning, or longer it thou wilt. I am ready to share with thee both bread and roof. Be one of us. Make trial of our life; of our wandering, poverty, and freedom. Tomorrow, at daybreak, in one van, we will go together. Choose thy trade: forge iron, or sing songs, leading the bear from village to village.”

Aleko: “I will remain.”

Zemphira: “He is mine; who shall take him from me? But it is late…. the young moon has set, the fields are hidden in darkness, and sleep overpowers me.”

Day breaks. The old man moves softly about the silent camp.

“Wake, Zemphira, the sun is rising; awake, my guest. ‘Tis time, tis time! Leave, my children, the couch of slothfulness.”

Noisily the clustering crowd expands; the tents are struck; the vans are ready to start. All is movement, and the horde advances over the desert.

Asses with panniers full of sportive children lead the way; husbands, brothers, wives, and daughters, young and old, follow in their wake. What shouting and confusion! Gypsy songs are mingled with the bear’s growling, impatiently gnawing at his chain. What a motley of bright-colored rags! The naked children! The aged men! Dogs bark and howl, the bagpipes drone, and the carts creak. All is so poor, so wild, so disorderly, but full of the life and movement ever absent from our dead, slothful, idle life, monotonous as the songs of slaves.

The youth gazes disheartened over the desert plain. The secret cause of his sadness he admits not even to himself. By his side is the dark-eyed Zemphira. Now he is a free inhabitant of the world, and radiant above him shines the sun in midday glory. Why, then, does the youth’s heart tremble—what secret sorrow preys upon him?

God’s little bird knows neither care nor labor,[Why should it strive to build a lasting nest? The night is long, but a branch suffices for its sleeping place. When the sun comes in its glory, birdie hears the voice of God, flutters his plumage, and sings his song. After spring, Nature’s fairest time comes hot summer. Late autumn follows, bringing mist and cold. Poor men and women are sad and dismal. To distant lands, to warmer climes beyond the blue sea, flies birdie to the spring. Like a little careless bird is the wandering exile. For him, there is no abiding nest, no home! Every road is his; at each stopping place is his night’s lodging. Waking at dawn, he leaves his day at God’s disposal, and the toil of life disturbs not his calm, indolent heart. At times, glory’s enchantment, like a distant star, attract his gaze; or sudden visions of luxury and pleasure float before him. Sometimes above his solitary head growls the thunder, and beneath the thunder, as beneath a peaceful sky, he sleeps serenely. And thus he lives, ignoring the power of blind treacherous Fate. But once, oh God! how passion played with his obedient soul! How it raged in his tormented breast! Is it long, and for how long, that it has left him calm? It will rage again; let him but wait!

Zemphira: “Friend, tell me, dost thou not regret what thou hast left forever?”

Aleko: “What have I left?”

Zemphira: “Thou knowest; thy people, thy cities.”

Aleko: “Regret? If thou knewest, if thou could’st imagine the confinement of our stifling towns! Their people crowded behind walls never breathe the cool breeze of the morning, nor the breath of spring-scented meadows. They are ashamed to love and chase away the thought. They traffic with liberty, bow their heads to idols, and beg for money and chains. What have I left? The excitement of treason, the prejudged sentence, the mob’s mad persecution or splendid infamy.”

Zemphira: “But their thou hadst magnificent palaces, many colored carpets, entertainments, and loud revels; and the maiden’s dresses are so rich!”

Aleko: “What is there to please in our noisy towns? The genuine love, no veritable joy. The maidens. How much dost thou surpass them, without their rich apparel, their pearls, or their necklaces! Be true, my gentle friend! My sole wish is to share with the love, leisure, and this self-sought exile.”

The Old Gypsy: “Thou lovest us, though born amongst the rich… But freedom is not always agreeable to those used to luxury. We have a legend:—

“Once a king banished a man from the South to live amongst us—I once knew but have forgotten his difficult name—though old in years he was youthful, passionate, and simple-hearted. He had a wondrous gift of song, with a voice like running waters. Everyone liked him. He dwelt on the banks of the Danube, harming no one, but pleasing many with his stories. He was helpless, weak, and timid as a child. Strangers brought him game and fish caught in nets. When the rapid river froze and winter storms raged high, they clad the saintly old man in soft warm furs. But he could never be inured to the hardships of a poor man’s life. He wandered about pale and thin, declaring that an offended God was chastening him for some crime. He waited, hoping for deliverance, and full of sad regret. The wretched man wandered on the banks of the Danube shedding bitter tears, as he remembered his distant home, and, dying, he desired that his unhappy bones should be carried to the South. Even in death, the stranger to these parts could find no rest.”

Aleko: “Such is thy children’s fate, O Borne, O world-famed Empire! Singer of love, singer of the gods, say what is glory? The echo from the tomb, the voice of praise continued from generation to generation, or a tale told by a gypsy in his smoky tent?”

Two years passed.

The peaceful gypsy band still wanders, finding everywhere rest and hospitality. Scorning the fetters of civilization, Aleko is free, like them; without regret or care, he leads a wandering life. He is unchanged, unchanged in the gypsy band. Forgetful of his past, he has grown used to a gypsy life. He loves sleeping under their tents, the delight of perpetual idleness, and their poor but sonorous tongue. The bear, a deserter from his native haunts, is now a shaggy guest within his tent. In the villages along the deserted route that passes in front of some Moldavian dwelling, the bear dances clumsily before a timid crowd and growls and gnaws his tiresome chain. Leaning on his staff the old man lazily strikes the tambourine; Aleko, singing, leads the bear; Zemphira makes the round of the villagers, collecting their voluntary gifts; when night sets in all three prepare the corn they have not reaped, the old man sleeps, and all is still… The tent is quiet and dark.

In the spring the old man is warming his numbed blood; at a cradle, his daughter sings of love. Aleko listens and turns pale.

Zemphira: “Old husband, cruel husband, cut me, burn me, I am firm, and fear neither knife nor fire. I hate thee, despise thee; I love another, and loving him will die.”

Aleko: “Silence, thy singing annoys me. I dislike wild songs.”

Zemphira: “Dislike them? And what do I care! I am singing for myself. Cut me, burn me, I will not complain. Old husband, cruel husband, thou shalt not discover him. He is fresher than the spring, warmer than the summer day. How young and bold he is! How much he loves me! How I caressed him in the stillness of the night! How we laughed together at thy white hair.”

Aleko: “Silence, Zemphira. Enough!”

Zemphira: “Then thou hast understood my song.”

Aleko: “Zemphira!”

Zemphira: “Be angry if thou wilt…. the song is about thee.” (She retires singing, “Old husband, &c.”)

The Old Gypsy: “Yes, I remember; that song was made in my time and has long been sung for folk’s amusement. Mariola used; it as we wandered over the Kagula Steppes, to sing it on winter nights. The memory of past years grows fainter hourly, but that song impressed me deeply.” . . . . . . . . . . . All is still. It is night, and the moon casts a sheen over the blue of the southern sky. Zemfira has awakened the old man.

“Oh, father! Aleko is terrible; listen to him! In his heavy sleep he groans and sobs.”

The Old Gypsy: “Do not disturb him, keep quiet. I have heard a Russian saying that at this time, at midnight, the house spirit often oppresses a sleeper’s breathing and before dawn quits him again. Stay with me.”

Zemphira: “Father, he murmurs Zemphira!”

The Old Gypsy: “He seeks thee even in his sleep. Thou art dearer to him than all the world.”

Zemphira: “I care no longer for his love; I am weary, my heart wants freedom. I have already—But hush! Does dost thou hear? He repeats another name.”

The Old Gypsy: “Whose name?”

Zemphira: “Dost thou not hear? The hoarse groan, the savage grinding of his teeth! How terrible! I will rouse him.”

The Old Gypsy: “No, don’t chase away the night spirit; it will leave him of its own accord!”

Zemphira: “He has turned, and raised himself; he calls me, he is awake. I will go to him. Good night, and sleep.”

Aleko: “Where hast thou been?”

Zemphira: “With my father. Some spirit has oppressed thee. In sleep, thy soul has suffered tortures. Thou didst frighten me; grinding thy teeth and calling out to me.”

Aleko: “I dreamt of thee, and saw as if between us… I had horrible thoughts.”

Zemphira: “Put no faith in treacherous dreams.”

Aleko: “Alas! I believe in nothing Neither in dreams, nor in sweet assurances, nor in thy heart.”

The Old Gypsy: “Young madman. Why dost thou sigh so often? We here are free. The sky is clean, and the women are famous for their beauty. Weep not. Grief will destroy thee.”

Aleko: “Father! she loves me no more.”

The Old Gypsy: “Be comforted, friend. She is but a child. Thy sadness is unreasonable. Thou lovest anxiously and earnestly, but a woman’s heart loves playfully. Behold, through the distant vault the full moon wanders free, throwing her light equally over all the world.

First, she peeps into one cloud, lights it brilliantly, and then glides to another, making to each a rapid visit. Who shall point out to her one spot in the heavens and say, ‘There shalt thou stay? Who to the young girl’s heart shall say, ‘Love only once and change not’? Be pacified.”

Aleko: “How she loved me! How tenderly she leaned upon me in the silent desert when we were together in the hours of the night! Full of child-like gaiety, how often, with her pleasant prattle or intoxicating caress, has she in an instant chased away my gloom! And now, Zemphira is false! My Zemphira is cold!”

The Old Gypsy: “Listen, and I will tell thee a story about myself. Long, long ago, before the Danube was threatened by the Muscovite (thou seest, Aleko, I speak of an ancient sorrow), at a time when we feared the Sultan who, through Boodjak Pasha, ruled the country from the lofty towers of Ackerman. I was young then, and my bosom throbbed with the passion of youth. My curly locks were not streaked with white. Among the young beauties, there was one… To whom I turned as to the sun, till at last, I called her mine. Alas! like a falling star, my youth swiftly sped. Still, briefer was our love. Mariola loved me but one year.”

“One day, by the waters of Kagula, we encountered a strange band of gypsies, who pitched their tents near ours at the foot of the hill. Two nights we passed together. On the third, they left, and Marioula forsook her little daughter and followed them. I slept peacefully. Day broke, and I awoke; my companion was not there. I searched, I called—no trace remained. Zemphira cried, I wept too! From that moment I became indifferent to all womankind. Never since has my gaze sought amongst them a new companion. My dreary hours I have spent alone.”

Aleko: “What! Didst thou not instantly pursue the ingrate and her paramour, to plunge thy dagger in their false hearts?”

The Old Gypsy: “Why should I? Youth is freer than the birds. Who can restrain love? Everyone has his turn of happiness. Once fled, it will never return.”

Aleko: “No, I am different. Without a struggle never would I yield my rights. At least, I would enjoy revenge. Ah, no! Even if I were to find my enemy lying asleep over the abyss of the sea, I declare that even then my foot should not spare him, but should unflinchingly kick the helpless villain into the depths of the ocean, and mock his sudden terrible awakening with a savage laugh of exultation. Long would his fall resound a sweet and merry echo in my ears.”

. . . . . . . A Young Gypsy: “One kiss, just one more embrace.”

Zemphira: “My husband is jealous and angry. I must go!”

The Young Gypsy: “Once more…. a longer one…. at parting.”

Zemphira: “Good-bye. Here he comes.”

The Young Gypsy: “Tell me. When shall we meet again?”

Zemphira: “To-night, when the moon rises over the hill beyond the tombs.”

The Young Gypsy: “She is deceiving me; she will not come.”

Zemphira: “Run—there he is! I will be there, beloved!”

Aleko sleeps, and in his mind, dim visions play. With a cry, he wakes in the dark, and, stretching out his jealous arm, clutches with a startled hand the cold bed. His companion is far away….. Trembling he sits up and listens… All is quiet! Fear comes upon him. He shivers, then grows hot. Rising from his bed, he leaves the tent, and, terribly pale, wanders around the vans. All is silent, the fields are still, and it is dark. The moon has risen in a mist, and the twinkling stars are scarcely seen. But on the dewy grass slight footprints can be discovered, leading to the tombs. With hurried tread, he follows on the path made by the ill-omened footmarks.

In the distance, on the roadside, a tomb shines white before him. Carried along by his hesitating feet, full of dread presentiment, his lips quivering, his knees trembling … he proceeds … when suddenly … can it be a dream? Suddenly he perceives two shadows close together, and hears two voices whispering over the desecrated grave.

The First Voice: “‘Tis time.”

The Second Voice: “Wait.”

The First Voice: “‘Tis time, my love.”

The Second Voice: “No, no! We will wait till morning.”

The First Voice: “‘Tis late already.”

The Second Voice “How timidly thou lovest! One moment more.”

The First Voice: “Thou wilt destroy me!”

The Second Voice: “One moment!”

The First Voice: “If my husband wakes and I am not——”

Aleko: “I am awake. Whither are you going? Don’t hurry; you both are well here—by the grave.”

Zemphira: “Run, run, my friend.”

Aleko: “Stop! Whither goest thou, my beautiful youth? Lie there!” (He plunges his knife into him.)

Zemphira: “Aleko!”

The Young Gypsy: “I am dying!”

Zemphira: “Aleko, thou wouldst kill him! Look, thou art covered with blood! Oh, what hast thou done?”

Aleko: “Nothing; thou canst now enjoy his love.”

Zemphira: “Enough, I do not fear thee! Thy threats I despise, and thy deed of murder I curse.”

Aleko: “Then die thyself!”

Zemphira: “I die, loving him.” . . . . . . . From the east the light of day is shining. Beyond the hill Aleko, besmeared with blood, sits on the grave-stone, knife in hand. Two corpses lie before him. The murderer’s face is terrible. An excited crowd of timid gypsies surrounds him. A grave is being dug. A procession of sorrowing women approaches, and each in turn kisses the eyes of the dead. The old father sits apart, staring at his dead daughter in dumb despair. The corpses are then raised, and into the cold bosom of the earth the young couple are lowered. From a distance Aleko looks on. When they are buried, and the last handful of earth thrown over them, without a word he slowly rolls from off the stone on to the grass. Then the old man approaches him, and says:

“Leave us, proud man. We area wild people and have no laws. We neither torture nor execute. We exact neither tears nor blood, but with a murderer we cannot live. Thou art not born to our wild life. Thou wouldst have freedom for thyself alone. The sight of thee would be intolerable to us; we are a timid, gentle folk. Thou art fierce and bold. Depart, then; forgive us, and peace be with thee!”

He ended, and with a great clamor, all the wandering band arose, and at once quitted the ill-fated camp and quickly vanished into the distant desert tract. But one van, covered with old rugs, remained in the fatal plain standing alone.

So, at the coming of winter and its morning mists, a flock of belated cranes rise from a field loudly shrieking and flying to the distant South, while one sad bird, struck by a fatal shot, with a wounded drooping wing, remains behind. Evening came. By the melancholy van, no fire was lighted, and no one slept beneath its covering of rugs that night.

THE END.

Did you know that spell-casting is one of the oldest spiritual practices in the world? That’s right! Ancient civilizations dating back to the first millennium

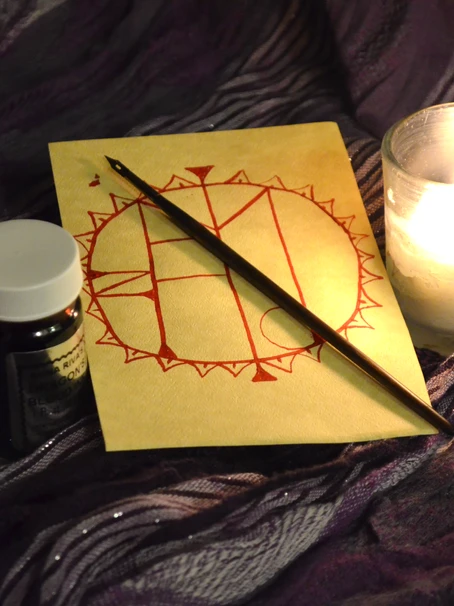

In the realm of majick and spellwork, sigils stand as powerful tools of manifestation and intention. These mystical symbols, crafted with intention and purpose, have

No ritual is complete without spell-casting! The practice of casting spells has been around for centuries. Many indigenous cultures continue to cast spells using their

I love these products! They come quickly and are well packaged! The Euphoria Oil smells amazing! Will be buying from this store again

The Euphoria ritual oil smells amazing! Everything came very well packaged especially from this oncoming summer heat.

Loving the prices! Some of the bundles are a little more than I can do right now but, for the most part I am truly pleased with my birthday present(s)

I absolutely LOVE these earrings! Items shipped fast, and were well packaged. I even got a a sample of body oil with purchase!

The packaging was beautiful! Instructions were easy to understand. I haven’t seen any results as of yet as I have only completed one ritual, but i can tell by the energy from it that it will work!

Subscribe to our newsletter and get in touch with the latest updates.

Welcome to Moonstruck Majick! We are an online boutique that supplies the witching world and alternative spirituality practitioners with ritual and spell supplies, curated from artisans across the United States.

© Copyright 2023 Moonstruck Majick . All Rights Reserved

© Copyright 2023 Moonstruck Majick . All Rights Reserved